In five years of being a founding principal, I have sent 14 emails to our team. Three of them were from before we opened. That’s an average of one email every 111 days or roughly 3 per year.

In that time, our school has grown from two employees to 60. We opened in the basement of a boys Catholic school, closed down, opened online 48 hours later, moved, started a new school year online, created an innovative “pod learning” program in the highest poverty and highest COVID case-count neighborhood in the city while maintaining 95%+ attendance on Zoom (and on camera!), then opened in-person in a new facility with 3x the student population we had the last time there was, you know, school. Our kids made some incredible and sustained progress.

Literally none of that would have been possible without some of the excellent lessons, tools, and mindsets we got from Maia Heyck-Merlin and her organization The Together Group.

Generally if Maia says to do something I say a. “thank you!” and b. “ok”.

Last year, Maia published this post about Slack, Maia’s Mailbag: Slack. . . love, hate, or somewhere in between? Which, as you might gather, is rather unflattering to the use of Slack in workplaces, particularly educational settings. When I found myself disagreeing, I definitely wanted to stop and consider. Then I sat on this post for a long time, until her team published another post about Slack, when I finally got my act in gear and dusted off this post.

There are a lot of reasons our team works the way it does, but I think Slack, and more importantly our consistent norms and usage of it, have been crucial to our team, and our lessons might be useful to others.

Since Day 1, our school has run on Slack.

Slack is the operating system of our school. If something can be accomplished using this tool, we’ll do that. If we can send a Slack instead of having a meeting, we will. If we can send a Slack instead of making a loudspeaker announcement, we will. (Fun fact – we have yet to use our public address system, although once a kid accidentally triggered it during a school-wide mock exam and you could just hear breathing and pencil scratching coming from every speaker in the building.)

In the ~1600 days since opening, we’ve sent a little over 1,000,000 Slack messages or ~625 messages per day. 70% are in established channels that have defined purposes or goals, like a team, project, event, or trip:

55%in public channels

30%in direct messages

15%in private channels

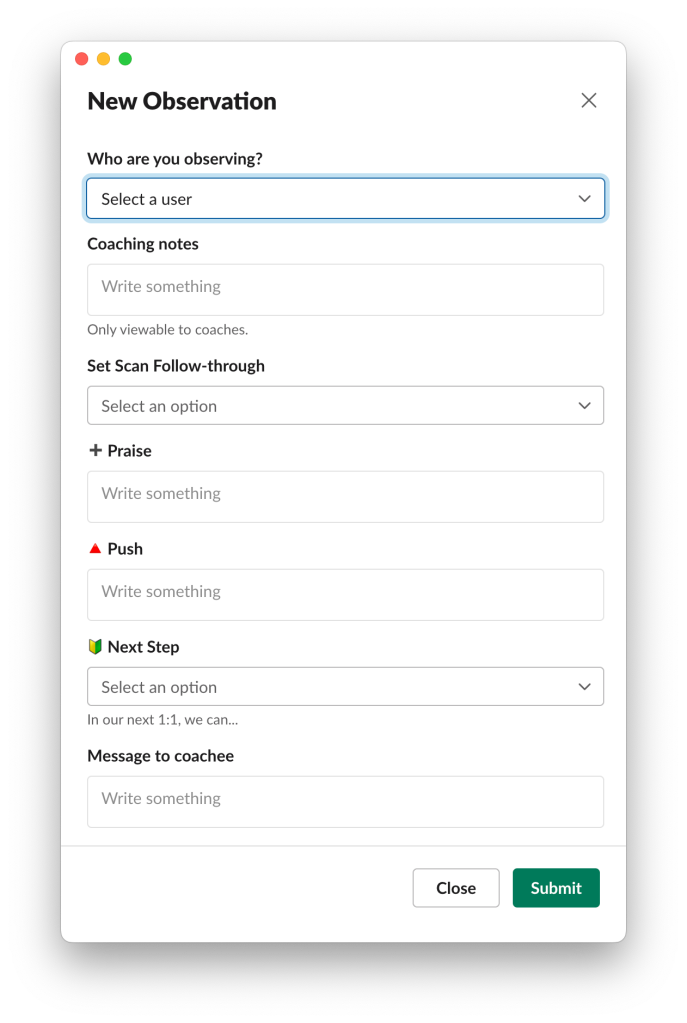

We do our Teacher Observation in Slack (more on that soon). We request pencils and rubber bands in Slack. We request help from the Restorative team and request PTO in Slack.

There are currently more Slack channels than people at Creo.

Norms

A few norms that keep us sane:

- Set and practice them → We do this during Summer PD/onboarding

- Hold to them → direct things to the right channel, and (gently) remind people of what to post where.

- Be person-centric → are you a leader asking someone to check in? Include 𝚈𝚘𝚞 𝚊𝚛𝚎 𝚗𝚘𝚝 𝚒𝚗 𝚝𝚛𝚘𝚞𝚋𝚕𝚎 in your message. When you read something that would benefit from acknowledgement, use an emoji to show you’ve read. A little 💛👍💡 goes a long way (and we have

318custom emoji to help with that!).

It starts in Summer PD (and is part of all mid-year employee onboarding).

It’s a school. Most communication is still (thankfully) face-to-face. However, it takes not time at all to Slack “hey can we check in at 2 to go over math data” rather than walking up to someone at 2pm and going “hey are you busy” (yes, I am, but I do love looking at math data!).

Types of communication

There are four primary methods of comms that we use Slack for:

1:1 ie DM’s.

This is easy, doesn’t require people to share personal information like a phone number, and is ideal for quickly checking in or collaborating.

1 → many

- restricted channels like #huddle-update. We have a few full-team channels with restrict posting so that certain teammates can send information to everyone, and everyone can respond in a thread, but not everyone can initiate a post. Ever been at a school with the Sunday Night Email™? We don’t do that. Every morning, we send a series of bullet points into #huddle-update at the start of our 7:17 Huddle that has quick hits and info for the day. A redacted example from last Friday:

Many:many

- #watercooler for fun things throughout the day

- Grade and content team channels for collaboration and sharing, like #team-history:

1 → follow-up workflows

Certain channels can only be posted in using “workflows” which work like forms. A few examples:

- #request-ops

- #request-restorative

- #request-coverage

- #observations

Which allow a team (whether it’s ops, coaching, leadership) to respond and triage requests and follow-up:

I’m writing more on how we use this for coaching observation, but that’s for another post.

Thinking Fast & Slow

Slack is great for some things, and crap for others. In general, I find it very useful for “thinking fast” – can I process and respond to the message in ≤ 30 seconds, and does it need to be responded to quickly? “Can I send this kid to the bathroom?” “Can someone support ____ in class?” Those are quick. “Let’s compare three prom venues for 7 months from now” is not, doesn’t need to be, and will certainly be pushed offscreen by incoming messages during a school day. For that, we use other tools like Google Docs, Basecamp, Notion, or other tools that are better for asynchronous planning and collaboration.

Slack doesn’t make our school what it is, but it enables things we value — clarity, consistency, urgency, kindness — to be accessible in the building, on the go, and in one place. I think having organizational values, systems, and norms that you practice is more important than the tool or tools you choose to use practice them with.

As a teacher, as a leader, as a coach, I don’t have to think about which comms platform to reach for, which gives me more time and bandwidth to think about what actually matters: the message.